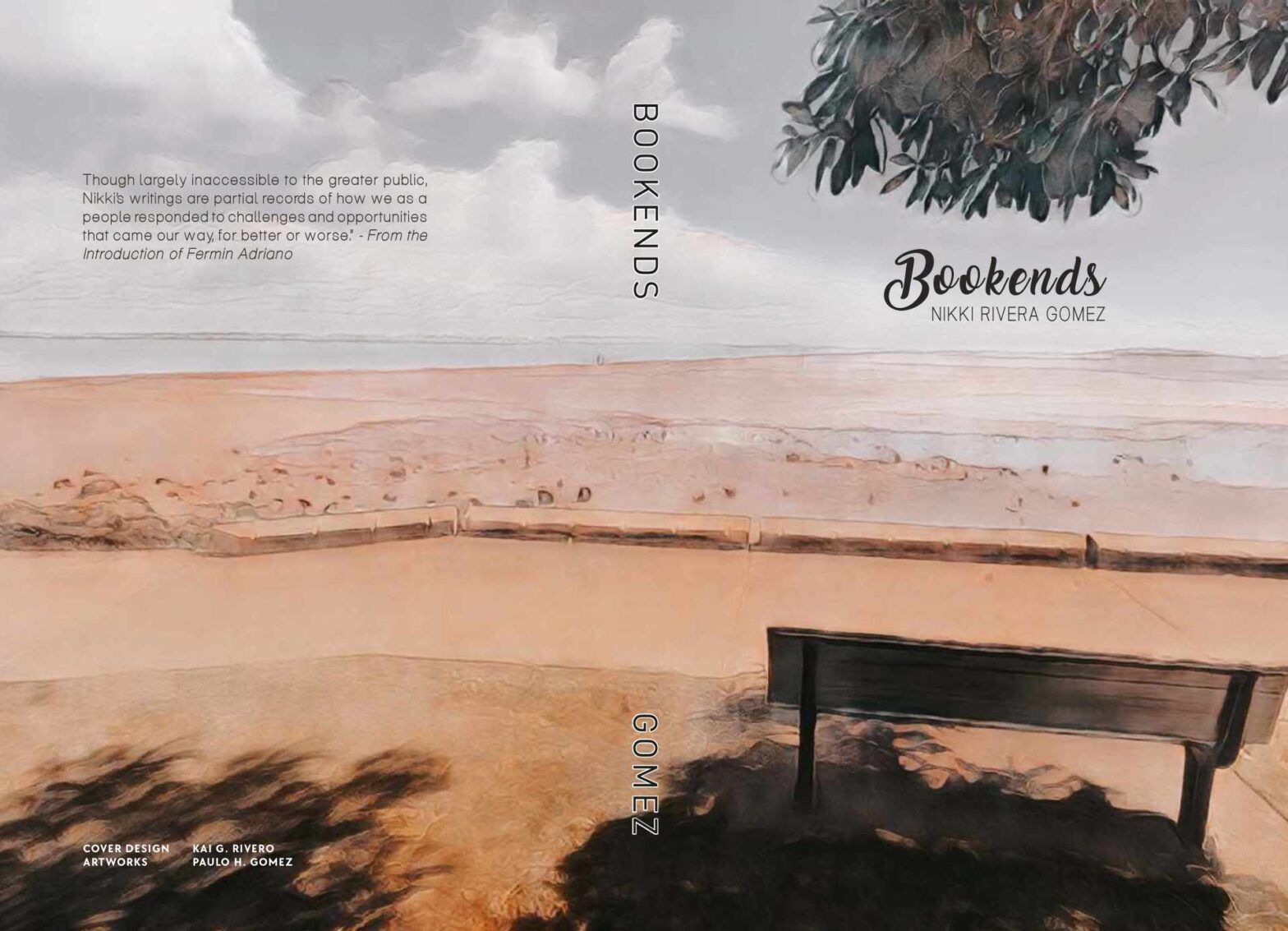

Bookends by Nikki Rivera Gomez

When I read a recent social media post announcing the imminent launch of the fourth book by Nikki Rivera-Gomez, a good friend from way back during my days as a development employee for the Cagayan de Oro-Iligan Corridor (CIC) Special Development Project, I excitedly volunteered to publish his story on it.

Nikki has previously authored three books published by the University of the Philippines Press: Coffee and Dreams on a Late Afternoon: Tales of Despair and Deliverance in Mindanao (2005); Mindanao on My Mind and Other Musings (2013), and Through the Years, Gently (2019).

Although I haven’t yet had the privilege of reading any of his previous publications, I already had a pretty good idea of the caliber of his literary chops, having enjoyed his contributed stories in MindaNews, and our collaborations in the Resurgent.PH website which he edited.

However, excitement quickly turned into dismay and trepidation when he asked me to write about it, and here I was thinking he would merely send me his press release on it. Like his bosom friend Dr. Fermin Adriano, former Undersecretary for Policy, Planning and Research o of the Department of Agriculture, a highly accomplished academician, scholar, writer and policy adviser to key government officials, I am always intimidated about writing about my friends’ works, especially those like Nikki whose friendship I value highly, fearing I might write something untoward which may not be taken for its intended purpose.

Fortunately, he gave me permission to quote some sections from Doc Fermin’s introduction to his book, saving me from eternal damnation. Indeed, the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

To start, “Bookends is composed of five sections: Narratives, People, Lineage, Sentiments, and Perseverance. It is a collection of around 57 essays starting in the early 80s and progressing until 2020. It practically covers the entire life span of Nikki, from a growing, temperamental, rebellious youth in his early 20s, to his senior years when idealism had been tempered with the mundane realities of existence, and when the valuation of happiness shifted from the requirements of “I” to the needs of our loved ones (wife, children, and grandkids).”

To further quote Doc Fermin: “(But) when I read the collections of musings from Nikki’s book, particularly the collections under the sections People and Lineage, I found them so refreshing and rejuvenating. They reminded me of my humanity as the same feeling of love and connection to family, acquaintances, and friends in the past and the present were movingly described by Nikki. I experienced the same in many instances in my life. Loved ones are treasures worth keeping and remembering for they are the composite elements that make us what we are today. They were also rejuvenating in the sense that they reminded me of my days of innocence when I dipped my toes in the realms of romanticism and idealism, unperturbed by the realities of a world where pragmatism becomes a convenient modality for survival, even prosperity.”

To further distance myself from the flames of eternal damnation, I asked Nikki where he first got the idea for Bookends.

He relates how it all began in 1978 and thereabouts, when he was a sophomore in the University of Mindanao, Majoring in English.

“Backdrop was world situation in turmoil. Banana republics mushrooming in Latin America, on the heels of Vietnam War and Woodstock, Dylan, Beatles, Martial Law…voracious reader of Readers Digest, Playboy (seriously this often misunderstood mag sparkled with literary gems, believe it or not) read up on Herman Khan, Ralph Nader.”

By the early 1980s, he was a writer and co-editor at Mindanao Sulu Secretariat for social action (Misssa), an apostolate of CBCP. Martial law was very much in place, and the Mindanao church under persecution.

“I felt like a church journalist if ever I knew one, heavily influenced by writers of the time: women journos like Letty Magsanoc, Sheila Coronel, Ceres Doyo, Cielo Buenaventura, the poet Mila Aguilar, and Pete Lacaba, Brillantes, Salanga, Coloma. My articles remained mostly straight news covering rallies, but I began news features in Misssa.”

By the 1990s, he was living in the fast lane eking out a living in Manila, Davao, government, private sector where he began cultivating media friends, wrote more straight news, a few features for PR clients.

It was during this time that he put up Mindanao Center for Peace and Development (MCPD) with the likes of Margie M. Floirendo, Tony Ajero, then Davao councilor the late Leo Avila as board trustees, to support local writers by giving out annual awards (the Alfredo Navarro Salanga Award for Excellence in Reporting, and the Bishop Bienvenido Award for Photojournalism).

After four years of this, he was “missing writings from the heart”, but thankfully the influence of his Lolo, author and newspaperman Godofredo Rivera, and aunt, the preeminent writer and publisher Gilda Cordero-Fernando, helped pull him back to literary nonfiction, and he put out the aforementioned three books by the UP Press from 2005-2019.

“Today, I’m content with writing about simple themes: Family, Friendships, Faith to still keep doing what we love to do I: To write, completely and with abandon, is more than just therapy. It’s a purpose. And that it’s invariably elusive is tragic. My readers complete me,” he muses.

“When someone agrees with something I’ve written- or even disagrees with it- I feel like I’m connected with my small neighborhood, with its thoughts and aspirations. Ang hirap i-explain exactly…when you feel that you matter. I’ve no regrets. I probably should have damned all and chosen to write at many points in my life. But we all have our reasons why we took this path over that. I’m only grateful I haven’t truly abandoned my writing, infantile as it really still is. There’s so much more stories to tell- or rather, write about.”

Nikki holds a graduate degree in Peace and Development from the Ateneo de Davao University. He is married to Aurea Hernandez-Gomez, with whom he has three children: Karla Kristina, Kevin Mikhail, and Paulo Miguel.

-30-